Groovy Trampoline Closure - a step into recursive closures

A few weeks ago an interesting question was asked on the StackOverflow. Someone experimented with a recursion in Groovy and stepped into Closure.trampoline() [1]. It quickly turned out that using TrampolineClosure makes a recursive execution slower. Is this a valid behavior, or do we do something wrong?

Why Closure.trampoline()?

Recursive algorithms in Groovy (or Java in general) are quite tricky. Every recursive call adds a frame to the call stack. If we make too many recursive calls, we can hit the call stack limit and cause StackOverflowError. We used to use recursive method calls, but the same problem applies to recursive closure calls. Consider the following example.

def factorial

factorial = { n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial(n - 1, acc * n ) } (1)

assert factorial(13) == 6227020800In this simple Groovy snippet we define a recursive closure call to compute the factorial of a given number. This recursive closure allows me to compute factorial of 706, but it hits the StackOverflowError for any number starting from 707.

This is where TrampolineClosure comes with a help.

Closures are wrapped in a

TrampolineClosure. Upon calling, a trampolinedClosurewill call the originalClosurewaiting for its result. If the outcome of the call is another instance of aTrampolineClosure, created perhaps as a result to a call to thetrampoline()method, theClosurewill again be invoked. This repetitive invocation of returned trampolinedClosuresinstances will continue until a value other than a trampolinedClosureis returned. That value will become the final result of the trampoline. That way, calls are made serially, rather than filling the stack.

Source: http://groovy-lang.org/closures.html#_trampoline

The above example refactored to the trampoline version may look like this:

def factorial

factorial = { n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial.trampoline(n - 1, acc * n ) }.trampoline()

assert factorial(13) == 6227020800The TrampolineClosure makes all recursive calls serial, so in this case computing factorial of numbers larger than 707 is doable.

The performance

What about the performance? Running a quick JMH benchmark shows that:

computing

factorial(500)without the trampoline takes 0.111 ms (in average) on my computercomputing

factorial(500)with the trampoline takes 0.196 ms (in average) on my computer

For a single call the difference is not huge. However, in the question asked on the StackOverflow we had to deal with a slightly different scenario. The person who asked this question compared the execution time of computing factorial 100,000 times for a pseudo-random number between 0 and 39.

| REMEMBER: The numbers below are just data. To gain reusable insights, you need to follow up on why the numbers are the way they are. Use profilers (see -prof, -lprof), design factorial experiments, perform baseline and negative tests that provide experimental control, make sure the benchmarking environment is safe on JVM/OS/HW level, ask for reviews from the domain experts. Do not assume the numbers tell you what you want them to tell. |

The benchmark

I created a benchmark that simulates a very similar scenario. In this test we benchmark the execution of calculating factorial 100,000 time using pseudo-random numbers from range <30,34>. This way we can eliminate anomalies (e.g. calculating factorial(0) or factorial(1)) and prevent JIT compiler from inlining method call with fixed argument.

| You can clone the JMH benchmark test source code from: wololock/groovy-closure-trampoline-example |

The benchmark tests the following scenarios:

calculating factorial using recursive closure call,

calculating factorial using recursive trampoline closure call,

calculating factorial using tail recursive method.

Each scenario is tested in the dynamic and statically compiled variant.

package bench

import groovy.transform.CompileStatic

import groovy.transform.TailRecursive

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Scope

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.State

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

class FactorialBench {

static final Random random = new Random()

static final int limit = 100000

@Benchmark

void a_standard() {

def factorial

factorial = { n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial(n - 1, acc * n ) }

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorial(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@Benchmark

@CompileStatic

void a_standard_sc() {

Closure factorial

factorial = { int n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial(n - 1, ((BigInteger) acc) * BigInteger.valueOf((long) n)) }

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorial(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@Benchmark

void b_trampoline() {

def factorial

factorial = { n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial.trampoline(n - 1, acc * n ) }.trampoline()

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorial(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@Benchmark

@CompileStatic

void b_trampoline_sc() {

Closure factorial

factorial = { int n, acc = 1G -> 1 >= n ? acc : factorial.trampoline(n - 1, ((BigInteger) acc) * BigInteger.valueOf((long) n)) }.trampoline()

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorial(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@Benchmark

void c_tailRecursive() {

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorialTailRecursive(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@Benchmark

@CompileStatic

void c_tailRecursive_sc() {

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

factorialTailRecursiveSC(30 + random.nextInt(5))

}

}

@TailRecursive

static factorialTailRecursive(n, acc = 1G) {

1 >= n ? acc : factorialTailRecursive(n - 1, n * acc)

}

@TailRecursive

@CompileStatic

static BigInteger factorialTailRecursiveSC(int n, BigInteger acc = 1G) {

1 >= n ? acc : factorialTailRecursiveSC(n - 1, acc * BigInteger.valueOf((long) n))

}

}I use JMH Gradle plugin, so executing the following benchmark looks like this:

$ ./gradlew clean jmh --no-daemonThe results

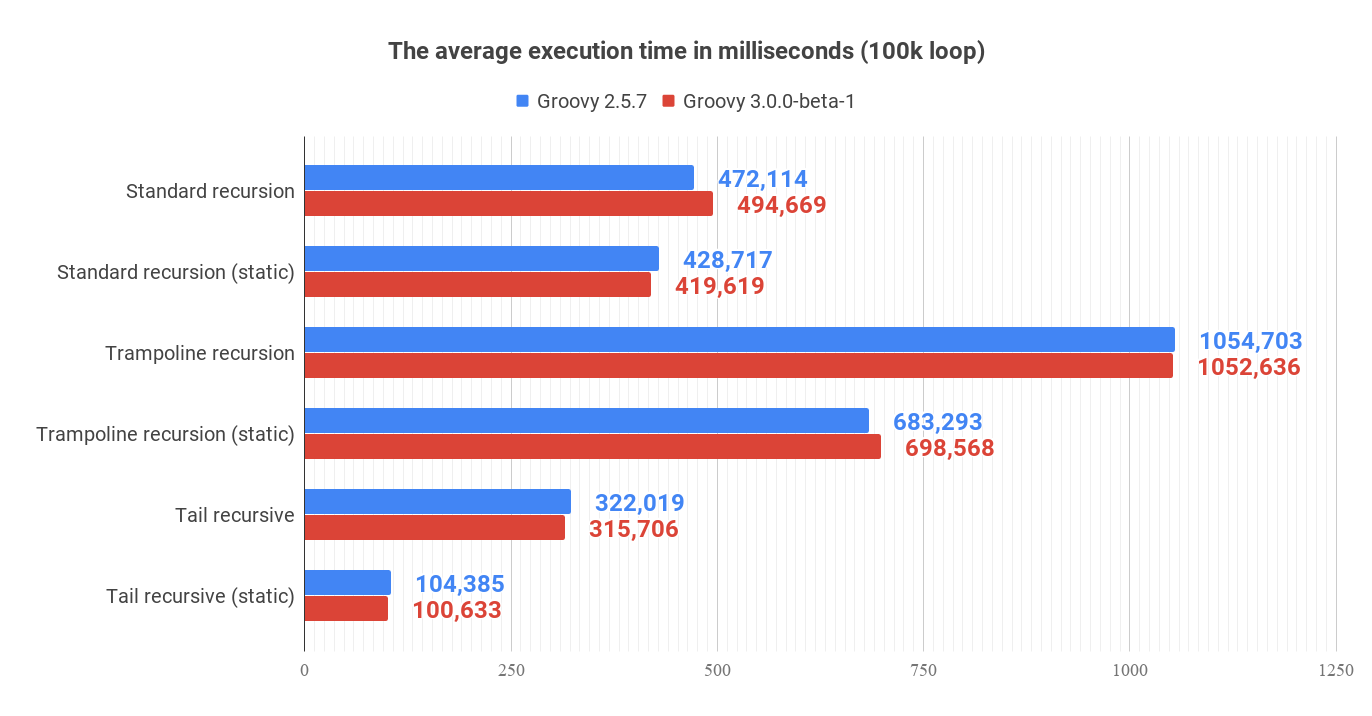

The execution of all benchmark scenarios takes about 8-9 minutes. I run it twice for Groovy 2.5.7 and for Groovy 3.0.0-beta-1 just to check if the upcoming version 3 introduces any performance improvements.

| Laptop specs: JDK 1.8.0_201 (Java HotSpot™ 64-Bit Server VM, 25.201-b09), Groovy 2.5.7, Intel® Core™ i7-4900MQ CPU @ 2.80GHz (4 cores, cache size 8192 KB), 16 GB RAM, OS: Fedora 29 (64 bit) |

1) Standard recursive closure

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FactorialBench.a_standard avgt 42 472,114 ± 1,315 ms/op

FactorialBench.a_standard_sc avgt 42 428,717 ± 1,063 ms/opThis is our starting point. We can see that running statically compiled code is approximately 9% faster.

And here is the stack profiler output.

....[Thread state: RUNNABLE]........................................................................

43,6% 43,6% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.metaclass.ClosureMetaClass.pickClosureMethod

21,6% 21,6% sun.reflect.DelegatingMethodAccessorImpl.invoke

21,2% 21,2% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.callsite.PojoMetaMethodSite$PojoCachedMethodSiteNoUnwrap.invoke

5,5% 5,6% groovy.lang.MetaMethod.doMethodInvoke

3,6% 3,6% groovy.lang.MetaClassImpl.invokeMethod

3,1% 3,1% sun.reflect.GeneratedMethodAccessor2.invoke

0,4% 0,4% java.math.BigInteger.multiply

0,3% 0,3% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.ArrayUtil.createArray

0,2% 0,2% java.util.Arrays.copyOf

0,2% 0,2% java.util.Arrays.copyOfRange

0,4% 0,4% <other>2) Trampoline closure

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FactorialBench.b_trampoline avgt 42 1054,703 ± 3,805 ms/op

FactorialBench.b_trampoline_sc avgt 42 683,293 ± 2,191 ms/opThe benchmark test shows that the (dynamic) trampoline variant of the factorial function is about 2.23 times slower compared to the standard recursive closure approach.

Here is the stack profiler output for the trampoline closure variant:

....[Thread state: RUNNABLE]........................................................................

22,6% 22,6% org.codehaus.groovy.reflection.ParameterTypes.isValidMethod

21,8% 21,8% org.codehaus.groovy.reflection.ParameterTypes.coerceArgumentsToClasses

15,5% 15,5% org.codehaus.groovy.reflection.ParameterTypes.correctArguments

11,5% 11,5% groovy.lang.Closure.<init>

9,4% 9,4% sun.reflect.DelegatingMethodAccessorImpl.invoke

8,5% 8,5% groovy.lang.TrampolineClosure.<init>

7,1% 7,1% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.metaclass.ClosureMetaClass.pickClosureMethod

0,4% 0,4% groovy.lang.MetaClassImpl.invokeMethod

0,3% 0,3% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.callsite.PojoMetaMethodSite$PojoCachedMethodSiteNoUnwrap.invoke

0,3% 0,3% java.math.BigInteger.multiply

2,6% 2,6% <other>There are two major differences between trampoline and the standard recursive closure:

Creating

TrampolineClosureobjects for each recursive call comes with a cost. In this specific case it took 210.8 ms (20% of the total time).Calling

Closure.trampoline(args)requires arguments coercion, which takes ~393 ms (37.3% of the total time).

Static compilation helps a bit - it executes in 683.293 ms average time. If we take a look at the call stack from the profiler, we see that static compilation removed the need of the arguments coercion. The main additional cost comes with the TrampolineClosure objects creation - it takes 185.172 ms (27,1% of the total time).

....[Thread state: RUNNABLE].....................................................................

29,2% 29,2% org.codehaus.groovy.reflection.ParameterTypes.isValidMethod

24,5% 24,5% java.math.BigInteger.multiply

16,7% 16,7% groovy.lang.Closure.<init>

10,4% 10,4% groovy.lang.TrampolineClosure.<init>

9,8% 9,8% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.metaclass.ClosureMetaClass.pickClosureMethod

4,0% 4,0% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.metaclass.MetaMethodIndex.getMethods

2,4% 2,4% org.codehaus.groovy.reflection.ParameterTypes.correctArguments

0,7% 0,7% sun.reflect.GeneratedMethodAccessor1.invoke

0,5% 0,5% groovy.lang.MetaClassImpl.invokeMethod

0,3% 0,3% java.util.Arrays.copyOf

1,3% 1,3% <other>3) Tail recursive method

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FactorialBench.c_tailRecursive avgt 42 322,019 ± 1,409 ms/op

FactorialBench.c_tailRecursive_sc avgt 42 104,385 ± 1,380 ms/opThe best performance comes with a tail recursive method. And it shouldn’t be a surprise - Groovy compiler compiles a method annotated with @TailRecursive to a bytecode that uses while-loop instead of the recursive calls. (Read more about in the Tail-recursive methods in Groovy post.) That is why the call stack is dominated by two operations:

java.math.BigIntegerobject initialization,and

java.math.BigInteger.multiply()method call.

....[Thread state: RUNNABLE]........................................................................

41,5% 41,5% java.math.BigInteger.<init>

26,8% 26,8% java.math.BigInteger.multiply

15,9% 15,9% java.lang.Integer.getChars

14,2% 14,2% java.lang.Integer.stringSize

0,5% 0,5% java.math.BigInteger.multiplyByInt

0,3% 0,3% bench.FactorialBench.factorialTailRecursive

0,2% 0,2% java.lang.Integer.toString

0,2% 0,2% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.typehandling.NumberMath.toBigInteger

0,2% 0,2% java.util.Arrays.copyOfRange

0,0% 0,0% org.openjdk.jmh.runner.BenchmarkHandler$BenchmarkTask.callThe statically compiled variant of the tail recursive method does even better. In this case it spends 97.1% of the time calling NumberMath.multiply.

....[Thread state: RUNNABLE]........................................................................

97,1% 97,2% org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.typehandling.NumberMath.multiply

1,1% 1,1% bench.FactorialBench.factorialTailRecursiveSC

0,8% 0,8% java.math.BigInteger.multiplyByInt

0,2% 0,2% java.math.BigInteger.valueOf

0,2% 0,2% bench.FactorialBench.c_tailRecursive_sc

0,2% 0,2% java.util.Arrays.copyOfRange

0,1% 0,1% java.lang.Thread.isInterrupted

0,1% 0,1% java.math.BigInteger.<init>

0,1% 0,1% java.lang.System.nanoTime

0,0% 0,0% sun.misc.Unsafe.unparkDoes Groovy 3.0.0-beta-1 do better?

Short answer - no. The results comparable. Even if Groovy 2.5.7 of 3.0.0-beta-1 does a little bit better in one variant or another, it doesn’t prove anything. The tendencies are the same in both cases.

Here you can find the full console output from the benchmark tests I use: |

Conclusion

The final question is - should we avoid using Closure.trampoline() then? Absolutely not. If you use recursive calls in the closure, you should consider using the TrampolineClosure to avoid hitting the call stack size limit. The cost of using TrampolineClosure in the statically compiled Groovy code becomes a trouble only when you need to handle hundreds of thousands calls that invoke recursive closure. However, in this case you can also consider refactoring to the tail recursive method call for the best performance. But remember what Donald Knuth said: "Premature optimization is the root of all evil." [2] Use whatever programming construction that works for you (and your team) best, and solve performance problems when they start occurring.

0 Comments